Overview: Psalms

The Synopsis

The Book of Psalms (Hebrew: Tehillim, meaning "Praises") functions as the divinely inspired prayer book and hymnal of ancient Israel, serving as a microcosm of the entire Old Testament—often called a "Little Bible." It is a sophisticated collection of 150 poems that navigate the vast landscape of human experience, shifting dynamically from the "pit" of agonizing lament to the "peak" of exuberant thanksgiving. Its rhetorical atmosphere is one of radical honesty and liturgical precision, transforming the history of God’s people into a living dialogue between the Creator and the creature. By bridging the gap between Torah (instruction) and life, the Psalter provides the vocabulary for faith, validating every human emotion while tethering the soul to the steadfast love (chesed) of God, ultimately pointing toward the restoration of the Davidic kingdom through the universal reign of Yahweh.

Provenance and Historical Context

Authorship & Date: The Psalter is a composite work compiled over nearly a millennium (c. 1406 BC to 400 BC). While 73 psalms are attributed to David ("A psalm of David"), the anthology includes contributions from Asaph, the sons of Korah, Solomon, Heman, Ethan, and Moses (Ps 90). The final canonical shaping likely occurred in the post-exilic period (5th–4th century BC) under the guidance of Ezra or similar scribal authorities, organizing disparate collections into the five-book structure we possess today.

The "Sitz im Leben" (Setting in Life): The primary setting was the cultic worship of Israel, centered first around the Tabernacle and later the Solomonic and Second Temples. However, the final "Setting in Life" is the post-exilic community. Having lost the physical monarchy and the glory of the Temple, the community used the Psalter to process their trauma, maintain their identity, and grapple with the delay of the Davidic promises while living under foreign rule.

Geopolitical & Cultural Landscape: The book spans the rise of the United Monarchy, the divided kingdom, the threat of the Neo-Assyrian and Babylonian empires, and the Persian restoration. It reflects a world where the physical survival of Israel was tied to their spiritual fidelity, and where Yahweh was presented not merely as a local deity but as the "Great King" challenging the supremacy of ANE gods like Baal and Marduk.

Audience: The recipients were the covenant people of Israel across generations. They were a community defined by their memory of the Exodus but frequently grappling with the cognitive dissonance of being God’s "treasured possession" while suffering under the boots of foreign empires or the oppression of wicked compatriots.

Psalms Structure

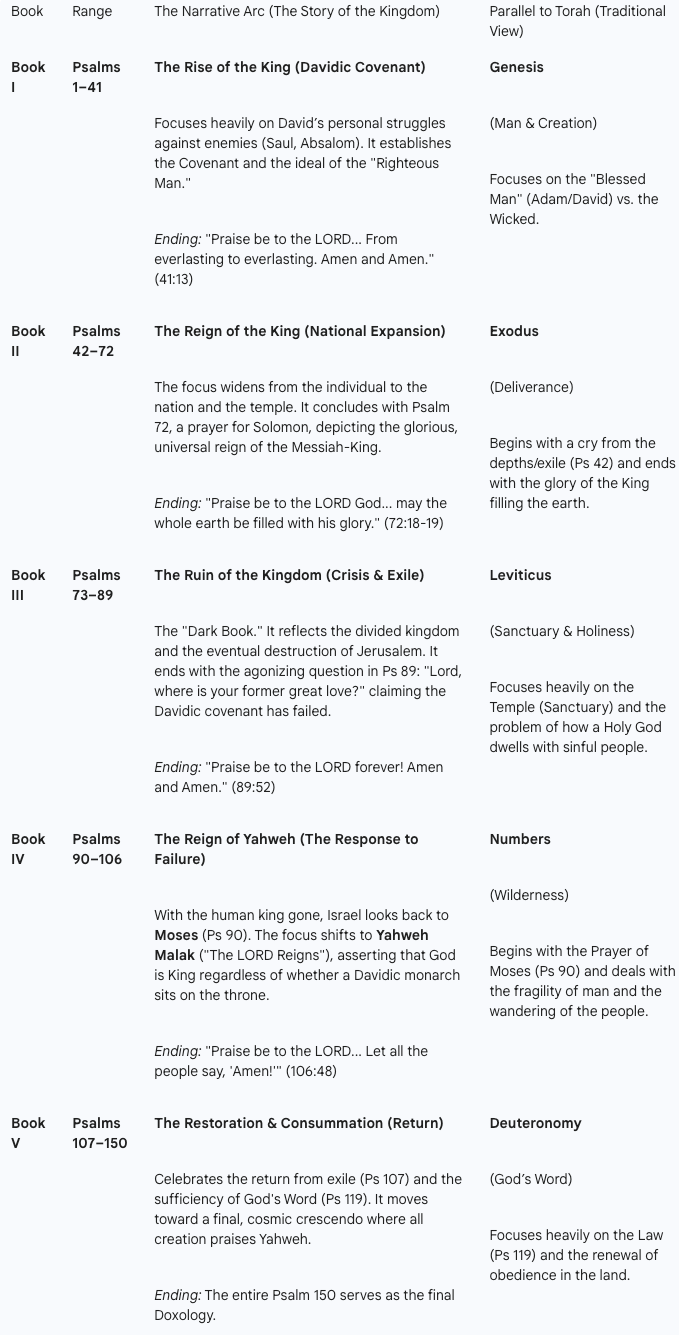

The Book of Psalms is not a random playlist of songs; it is structured into five distinct "Books" (or scrolls). This arrangement was likely a deliberate editorial decision to mirror the Five Books of Moses (The Pentateuch), presenting the Psalter as a "New Torah" (Instruction) for the people of God.

Each book concludes with a Doxology—a short hymn of praise that serves as a textual marker (e.g., "Praise be to the LORD... Amen and Amen").

Here is the architectural breakdown of the Five Books:

In spite of this five-book division, the Psalter was clearly thought of as a whole, with an introduction (Ps 1-2) and a conclusion (Ps 146-150)

Critical Issues (Scholarly Landscape)

Methodological Shift (Form vs. Canon): The most significant development in modern scholarship is the move from Form Criticism (associated with Hermann Gunkel, focusing on the isolated cultic setting of individual psalms) to Canonical Criticism (associated with Brevard Childs and Gerald Wilson). The focus has shifted from "Where was this psalm used?" to "Why was it placed here in the book?"

The "Shape of the Psalter": Arising from Canonical Criticism, this debate posits that the five-book structure is not a random anthology but a purposefully edited narrative. The consensus among these scholars is that the arrangement traces the failure of the human Davidic monarchy (Books I–III) and shifts the focus toward Yahweh’s eternal Kingship (Books IV–V) as the answer to the exile.

The Status of Superscriptions: A persistent debate concerns the titles (e.g., "A Psalm of David"). Conservative scholars view them as historically reliable and hermeneutically essential (providing the context), while critical scholars often dismiss them as later midrashic additions not original to the text. Of the 150 psalms, only 34 lack superscriptions of any kind.

The contents of the superscriptions vary but fall into a few broad categories:

- Author

- Name of collection

- Type of psalm

- Musical notations

- Liturgical notations

- Brief indications of occasion for composition

Genre and Hermeneutical Strategy

Psalms Genres

Genre Identification: The primary genre is Hebrew Poetry.

Analysis of form of content has given rise to three main functional genres, which describe the action or mood of the psalm:

- Hymns of Praise

- Lament (Individual/Corporate)

- Thanksgiving

There are other types of psalms or thematic subsets, which describe the specific topic or content:

- Royal/Messianic Psalms

- Wisdom/Torah Psalms

- Imprecatory Psalms

These thematic subsets are considered subsets of the three main types.

Hermeneutical Strategy

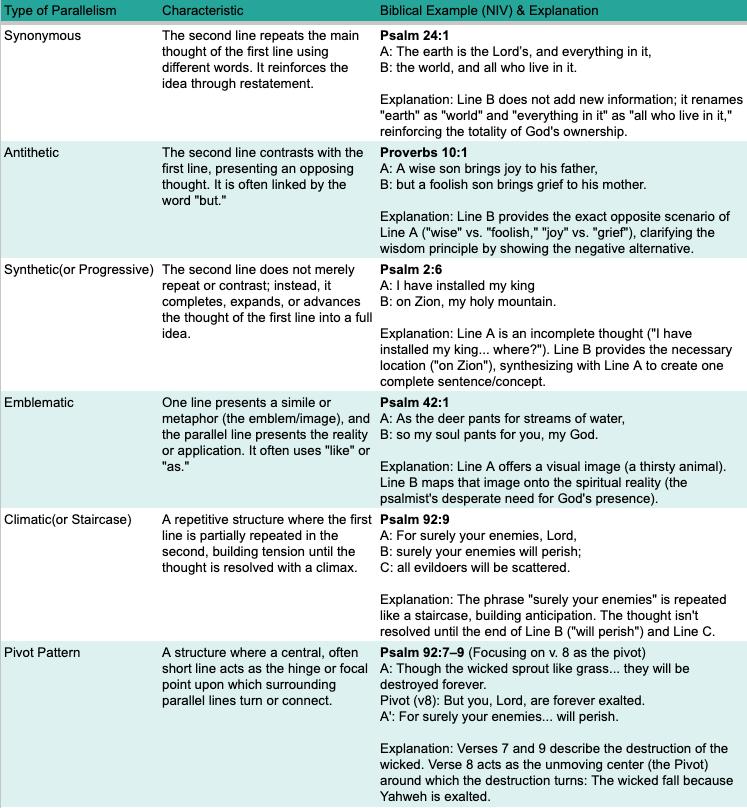

The Reading Strategy: The reader must engage the Psalms through the lens of Hebrew Parallelism.

Hermeneutically, one must distinguish between the "Voice of the Psalmist" (human speech to God) and the "Word of God" (God's speech to man). The Psalms are "inspired models of prayer," meaning they validate raw human emotions (including anger and despair) without necessarily endorsing every sentiment as a prescriptive moral command for the believer (e.g., Psalm 137).

Covenantal and Canonical Placement

Covenantal Context: The Psalter is anchored in the tension between two major covenants: the Mosaic Covenant (emphasizing Torah obedience, seen in Pss 1, 19, 119) and the Davidic Covenant (emphasizing the eternal throne, seen in Pss 2, 89, 132). The theological crisis of the book arises when the "unconditional" promise to David seems to collide with the "conditional" reality of the exile.

Intertextuality: The Psalms function as an "Echo Chamber" of the Old Testament. The book is structured into five parts to mirror the Pentateuch (Torah), framing the Psalms as a "Second Torah" or a meditation on God's instruction. It leans heavily on the Exodus narrative and specifically the revelation of God's character in Exodus 34:6-7 (chesed and rachum), using these attributes as the basis for appeal during national crisis.

Key Recurrent Terms

Chesed (Steadfast love / Covenant loyalty)

Significance: This is the theological heartbeat of the Psalter. It refers not merely to emotion but to God’s tenacious, legally binding commitment to His people. When the psalmist is in the "pit," chesed is the specific attribute invoked to demand rescue, grounding salvation in God's integrity rather than human merit.

Mishpat (Justice / Judgment)

Significance: Often paired with righteousness (tzedakah), this term refers to God’s restorative justice. In the Psalms, mishpat is active; it is the act of putting the world right by vindicating the oppressed, feeding the hungry, and halting the violence of the wicked.

Selah (Pause / Musical Interlude)

Significance: Appearing 71 times, this term serves as a structural and liturgical marker. It instructs the worshiper to pause and weigh the gravity of the preceding statement, emphasizing that the Psalms are designed for meditation, not just recitation.

Ashre (Blessed / Happy)

Significance: The very first word of the book (Ps 1:1). It defines the "flourishing life" not as material prosperity, but as a state of alignment with God's instruction (Torah). It frames the entire Psalter as a guide to true human happiness.

Chasah (To take refuge)

Significance: This verb describes the fundamental posture of the believer. It is the active, volitional choice to flee to Yahweh for protection rather than trusting in "princes," "horses," or "chariots."

Tehillim (Praises)

Significance: The Hebrew title for the book. It denotes that the ultimate goal of all human experience—even the darkest lament—is to arrive at the glorification of God.

Key Thematic Verses

Psalm 1:1–2

"Blessed is the one who does not walk in step with the wicked or stand in the way that sinners take or sit in the company of mockers, but whose delight is in the law of the LORD, and who meditates on his law day and night."

Significance: These verses act as the "Gateway" to the entire Psalter. They establish the "Two Ways" (The Righteous vs. The Wicked) and posit that the secret to stability in a chaotic world is deep, murmuring meditation on God's Torah.

Psalm 89:46, 49

"How long, LORD? Will you hide yourself forever? How long will your wrath burn like fire? ... Lord, where is your former great love, which in your faithfulness you swore to David?"

Significance: This verse marks the theological crisis of the book (end of Book III). It voices the tension between God's promise of an eternal throne and the historical reality of exile, setting the stage for the shift to Yahweh's direct kingship in Book IV.

Psalm 145:13

"Your kingdom is an everlasting kingdom, and your dominion endures through all generations. The LORD is trustworthy in all he promises and faithful in all he does."

Significance: This encapsulates the resolution of the book's tension. After the failure of human kings, the Psalter concludes that Yahweh’s reign is the only true eternal kingdom, providing the ultimate comfort for the believer.

Major Theological Themes

The Universal Kingship of Yahweh (Yahweh Malak): The central theological claim of the Psalter is that "The LORD Reigns." Despite the rise of empires or the fall of Jerusalem, the Psalms assert that God is currently enthroned over the flood. This sovereignty is not abstract; it is the guarantee that order will eventually swallow chaos.

The Theology of the "Pit" (The Validity of Lament): Uniquely, the Psalms teach that "complaint" is a legitimate form of worship. By including laments, the Canon validates the experience of God’s perceived absence ("Deus Absconditus"). It teaches that bringing one's anger, doubt, and sorrow to God is a higher act of faith than silent withdrawal or stoicism.

The Torah as Refuge (Sapiential Piety): The Law is portrayed not as a burden but as a gift of light and life. The "Righteous" (tsaddiq) are distinguished from the "Wicked" (rasha) not by perfection, but by their orientation toward God's Word. Meditation on Torah is presented as the primary means of spiritual survival.

Zion as the Axis Mundi: Jerusalem (Zion) is viewed not just as a capital city but as the intersection of heaven and earth—the dwelling place of God. It represents the security of the believer, foreshadowing the New Jerusalem where God dwells with man.

Christocentric Trajectory

The Macro-Tension: A primary way the Psalms point ahead to the coming Messiah is through their idealized portrait of Israel's king, often with a focus on the Davidic dynasty. This portrait emerges primarily in a set of Psalms identified as "royal Psalms." The picture of this prototypical king extends from his enthronement to his just and merciful rule to his victories in battle because of God's blessing. This idealized figure trusts in the Lord and is utterly faithful to him. This idealization of a Davidic king provides the Messianic raw material for NT writers, who often draw upon these royal psalms to show how Jesus, as Messiah, is the ultimate and unique Davidic king.

The primary tension in the Psalms is the apparent failure of the Davidic Covenant. As the book progresses, the earthly Davidic kings fail, the nation goes into exile, and the "throne" seems lost (Ps 89). The tension is: How will God fulfill His sworn promise to David of an eternal kingdom?

The Resolution: Jesus Christ fulfills the Psalter through His Threefold Office, resolving the tension of the "missing king."

Typological Connections

The True King (Royal): Jesus is the "Son" of Psalm 2 and the "Lord" of Psalm 110. His resurrection validates Him as the one who restores the fallen tent of David and reigns forever.

The Suffering Righteous One (Lament): Jesus appropriates the language of the "Pit." His cry on the cross (Psalm 22:1) identifies Him as the ultimate Sufferer who takes the curses of the Psalms upon Himself.

The Leader of Praise: In His resurrection, Jesus becomes the "Chief Musician" (Hebrews 2:12), leading the congregation in the new song of redemption that the Psalter anticipates.

Detailed Literary Architecture

Book I: The Davidic Struggle and Personal Deliverance (Psalms 1–41)

A. The Introduction: The Torah and the Messiah as the dual keys to the Psalter (1–2).

B. The Conflict: Focuses on David’s personal trials against enemies and the "wicked."

C. The Resolution: Reliance on Yahweh as "Shield" and "Rock," concluding with a doxology (41).

Book II: The National Devotion and the Expansion of Hope (Psalms 42–72)

A. The Lament: Opens with the sons of Korah crying out from exile/distance (42–44).

B. The King: Expands the scope to the community and the city of God.

C. The Climax: Concludes with the glorious, universal reign of the Solomon-like King (72).

Book III: The Crisis of the Covenant and the Dark Night (Psalms 73–89)

A. The Question: Begins with Asaph questioning the prosperity of the wicked (73).

B. The devastation: Reflects the destruction of the Temple and the reality of judgment.

C. The Collapse: Ends with the haunting question of Psalm 89, wondering if God's covenant with David has failed.

Book IV: The Sovereignty of Yahweh as the Answer to Exile (Psalms 90–106)

A. The Pivot: Reaches back to Moses (90), reminding Israel that God was their King before the monarchy existed.

B. The Proclamation: A collection of "Enthronement Psalms" (93, 96–99) asserting Yahweh Malak—"The LORD Reigns!"

C. The History: Reviews Israel’s history to show that God has always been faithful despite their rebellion (105–106).

Book V: The Restoration, the Word, and the Final Hallelujah (Psalms 107–150)

A. The Return: Celebrates the gathering of the redeemed from the lands of exile (107).

B. The Law: Places the massive Psalm 119 at the center, affirming Torah as the guide for the restored community.

C. The Ascent: The Songs of Ascents (120–134) for pilgrims traveling to Zion.

D. The Doxology: The book concludes with five "Hallelujah" psalms (146–150), where all creation is summoned to praise the King.