Overview: Daniel

The Synopsis

The Book of Daniel serves as the quintessential manual for "faithful subversion" and a theological survival guide for living under the shadow of pagan empire. Set against the bleak backdrop of the Babylonian Exile, the book functions as a literary diptych: the first half (Chapters 1–6) utilizes heroic court narratives to demonstrate God’s sovereignty over earthly monarchs, while the second half (Chapters 7–12) employs vivid, hallucinatory apocalyptic visions to reveal the spiritual warfare behind human history. The rhetorical atmosphere shifts from the tense, high-stakes drama of the royal court to the awe-inspiring vistas of the heavenly throne room. Its primary contribution to the Biblical Canon is the revelation that "the Most High is sovereign over the kingdoms of men" (Daniel 4:17), providing the essential theological vocabulary for the "Kingdom of God" and introducing the "Son of Man"—the ultimate solution to the beastly nature of human rule.

Provenance and Historical Context

Authorship & Date: Internal evidence strongly attributes the book to Daniel, a Judean of noble birth carried into exile in 605 BC (Daniel 12:4).

The "Conservative" view maintains a 6th-century BC date, accepting the detailed prophecies as genuine predictive revelation.

The "Critical" consensus typically dates the final form to the 2nd century BC (c. 167–164 BC). Because of the highly specific prophecies related to the Maccabean period (second century BC), some hold that the book was written in the mid-second century, during the period of the oppression of the Jews by Antiochus IV. Therefore all fulfilled predictions in Daniel, it is claimed, had to have been composed no earlier than the Maccabean period, after the fulfillments had taken place. But unless one rejects all long-range predictive prophecy, this conclusion is unnecessary for the following reasons:

- The adherents of the late-date view usually maintain that the four empires of chs. 2 and 7 are Babylonia, Media, Persia and Greece. But in the mind of the author, “the Medes and Persians” (5:28) together constituted the second in the series of four kingdoms (2:32–43). Thus it becomes clear that the four empires are the Babylonian, Medo-Persian, Greek and Roman.

- The language itself argues for a date earlier than the second century. Linguistic evidence from the Dead Sea Scrolls (which furnish authentic samples of Hebrew and Aramaic writing from the third and second centuries BC) demonstrates that the Hebrew and Aramaic chapters of Daniel must have been composed centuries earlier. Some of the technical terms appearing in ch. 3 were already so obsolete by the second century BC that translators of the Septuagint (the pre-Christian Greek translation of the OT) translated them incorrectly.

- Several of the fulfillments of prophecies in Daniel could not have taken place by the second century anyway, so the prophetic element cannot be dismissed. The symbolism connected with the fourth kingdom makes it unmistakably predictive of the Roman Empire (2:33; 7:7, 19), which did not take control of Syro-Palestine until 63 BC.

- A plausible interpretation of the prophecy concerning the coming of “the Anointed One.” Daniel was studying the scrolls of Jeremiah, which predicted that the desolation of Jerusalem would last strictly seventy years. Realizing this timeframe was nearing its end (c. 538 BC), Daniel prayed for the promised restoration. The angel Gabriel interrupted to reveal a "Hermeneutical Expansion": while the physical exile was ending (the people could return), the spiritual exile (the resolution of sin) would not end after 70 years, but would be extended seven-fold to "Seventy Sevens" (490 years) before the true Anointed One would secure everlasting righteousness. This aligns with the time period of Jesus.

The "Sitz im Leben" (Setting in Life): The book addresses the "identity crisis" of the Diaspora. Following the destruction of the Temple and the Davidic throne, the Judean exiles faced an ontological threat: Had Yahweh been defeated by the gods of Babylon? The text was written to sustain faith during a prolonged period of "Gentile Times," where God’s people were politically marginalized and culturally pressured to assimilate.

Geopolitical & Cultural Landscape: The setting spans the transition from the Neo-Babylonian Empire (under Nebuchadnezzar and Belshazzar) to the Medo-Persian Empire (under Cyrus and Darius). Culturally, this was an environment of "totalitarian pluralism"—the empire tolerated various ethnicities and local deities provided they adopted the Chaldean language, education, and ultimate allegiance to the state cult.

Audience: The original recipients were a displaced minority living in a "post-theocratic" world. They struggled with the fear of national extinction and the sociological tension of being "in the world but not of it." They needed assurance that the Abrahamic promises remained valid even when the throne in Jerusalem sat empty.

Critical Issues (Scholarly Landscape)

The Bilingual Composition: The book features a unique "linguistic sandwich," beginning in Hebrew (1:1–2:4a), shifting to Aramaic (2:4b–7:28), and returning to Hebrew (8:1–12:13). This suggests a structural intent: the central Aramaic section (the lingua franca of the time) addresses the universal destiny of Gentile nations, while the Hebrew "bookends" focus on the specific covenantal future of Israel.

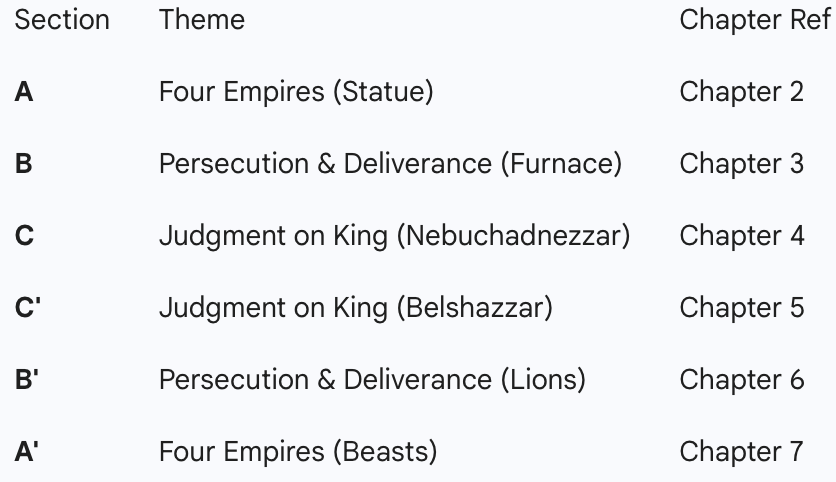

This Aramaic center is not random; it forms a perfect Chiasm (A-B-C-C'-B'-A').

Chapters 2 and 7 correspond (Four Empires), Chapters 3 and 6 correspond (Rescue from Execution), and Chapters 4 and 5 correspond (Judgment on Kings). This structure highlights the central theological axis: God’s sovereignty over Gentile kings.

The Identity of Darius the Mede: The figure of Darius (6:1) remains a significant historical crux, as he is not yet clearly identified in extra-biblical records. This has led to various scholarly theories, most notably that "Darius" is either a throne name for Cyrus the Great or a reference to the governor Gubaru.

Genre and Hermeneutical Strategy

Genre Identification: Daniel is a hybrid of Court Narrative (didactic stories of wisdom and testing, Ch. 1–6) and Apocalyptic Literature (highly symbolic visions of the end of the age, Ch. 7–12).

The Reading Strategy: A dual-lens hermeneutic is required:

- Narrative Lens (1–6): Focus on the model of "faithful presence" or "principled flexibility." The reader must distinguish between cultural contextualization (accepting a new name/education) and moral compromise (refusing royal food/idolatry).

- Apocalyptic Lens (7–12): Apply a "telescoping" view. Apocalyptic symbols often possess a dual fulfillment: a near-term historical referent (e.g., Antiochus IV Epiphanes) and a far-term eschatological referent (the final "Antichrist"). One must avoid literalism (e.g., expecting literal monsters) and focus on the theological reality the symbols represent (e.g., the predatory nature of empire).

Covenantal and Canonical Placement

Covenantal Context: Daniel operates under the Mosaic Covenant—specifically the curses of Deuteronomy 28 regarding exile for disobedience—but looks forward to the fulfillment of the Davidic Covenant. Since the Davidic King is absent, Daniel emphasizes God’s direct rule as the "King of Heaven" and introduces the "New Covenant" hope of the resurrection of the dead (Daniel 12:2).

Intertextuality: The book is deeply "Scripture-saturated." It relies heavily on Jeremiah (specifically the prophecy of the seventy-year exile, Dan 9:2) and Genesis (contrasting the "Beasts" rising from the chaos-sea with the "Son of Man" who fulfills the dominion mandate). It serves as the foundational "lexicon" for the New Testament Book of Revelation, which adopts Daniel’s symbols to describe the final victory of the Lamb.

Key Recurrent Terms

Malku / Malkut (Kingdom / Sovereignty / Dominion)

Significance: Appearing over 50 times (predominantly in the Aramaic section), this is the theological "north star" of the book. It establishes the central polemic: while earthly monarchs like Nebuchadnezzar claim absolute malku, the text relentlessly asserts that "the Most High is sovereign over the kingdoms of men." It forces the reader to distinguish between the fragile, temporary regimes of history and the "everlasting dominion" of God.

Raz (Mystery / Secret)

Significance: A Persian loanword used to describe a divine secret that remains "locked" to human reason, astrology, or political acumen. It underscores the failure of Babylonian "wisdom" (the magi) and highlights that the true meaning of history is only accessible through revelation. God is the "Revealer of Mysteries" who discloses the end from the beginning.

Qaddishin (Holy Ones / Saints)

Significance: This term identifies the community of the faithful who suffer under the "Beasts" but are ultimately vindicated by the Divine Court. It redefines the identity of the exiles: they are not merely refugees of a defeated nation, but the "set apart" people of the Most High who are destined to inherit the Kingdom.

Key Thematic Verses

Daniel 2:44

"In the time of those kings, the God of heaven will set up a kingdom that will never be destroyed, nor will it be left to another people. It will crush all those kingdoms and bring them to an end, but it will itself endure forever."

Significance: This serves as the book's "Thesis Statement" regarding the philosophy of history. It declares that all earthly regimes are strictly penultimate; the ultimate destiny of the world is not "Empire" but the unshakable Kingdom of God.

Daniel 7:13–14

"In my vision at night I looked, and there before me was one like a son of man, coming with the clouds of heaven... He was given authority, glory and sovereign power; all nations and peoples of every language worshiped him."

Significance: This is the Christological heart of the book. It introduces the solution to the "beastly" nature of human government: a human figure ("Son of Man") who receives divine prerogatives and establishes a universal, humane rule.

Major Theological Themes

The Absolute Sovereignty of God (The Pantocrator): Daniel moves beyond the concept of God as a local "tribal deity" to reveal Him as the Ruler of All. He humbles kings, sets up authorities, and deposes them at His will. History is not a series of accidents but a directed "drama" under divine supervision, designed to provide "psychological liberation" for a captive people.

The Beastly Nature of Autonomy: The visions in Chapters 7 and 8 portray human empires not as noble civilizations but as predatory, chaotic "beasts" rising from the sea. This offers a profound theological critique: when a state or ruler rejects God’s rule, they lose their humanity and become monstrous.

Wisdom as "Faithful Subversion": The book redefines wisdom (chokmah) as the ability to navigate a hostile culture without compromising covenantal identity. It promotes a "third way" between total assimilation (becoming Babylonian) and violent revolution—a strategy of "faithful presence" where the believer excels in civic duty but refuses ultimate allegiance to the state.

The Reality of Unseen Conflict: Daniel pulls back the curtain on the spiritual dimension of geopolitics (e.g., the "Prince of Persia" in Chapter 10). It teaches that the visible struggles of history are reflections of a "war in the heavens," where God’s angelic messengers act on behalf of His people.

Christocentric Trajectory

The Macro-Tension: The "shadow" in Daniel is the apparent triumph of the "Beasts" over the "Saints." The Davidic throne is empty, the Temple is in ruins, and the world is ruled by predatory powers that "devour the whole earth." The tension lies in how a scattered, powerless people can ever inherit an eternal, global kingdom when the "times of the Gentiles" seem unending.

The Resolution: Jesus Christ fulfills this tension through the Office of the Son of Man.

- Typology: He is the "Stone cut without human hands" (Dan 2:34) that shatters the statue of human pride.

- Identification: Jesus explicitly adopts the title "Son of Man" (Matt 26:64) to claim the dominion of Daniel 7. Unlike the beasts who take power by force, the Son of Man receives power through suffering and vindication.

- Presence: He is typified as the "Fourth Man" in the fiery furnace (Dan 3:25), demonstrating that God does not always save His people from suffering, but saves them in it through His presence.

Detailed Literary Architecture

I. THE PROLOGUE (Hebrew Section)

Focus: The Test of Covenant Identity

Chapter 1: The Crucible of Culture The book opens with the immediate crisis of the Exile. Daniel and his friends face the "Test of Assimilation" (1:1–7) regarding their names and diet. They respond with the "Resolution of Holiness" (1:8–21), proving that faithful subversion is possible in a pagan court.

II. THE ARAMAIC CHIASM (Chapters 2–7)

Focus: The Sovereignty of God over Gentile Powers Structure: This section forms a perfect literary mirror (Chiasm) centering on the humbling of human pride.

[A] The Four Empires: The Statue (Chapter 2) Nebuchadnezzar dreams of a multi-metal statue representing four successive empires. Human wisdom fails to interpret it, but God reveals that a "Stone cut without hands" will destroy the statue and establish an eternal kingdom.

[B] Persecution & Deliverance: The Fiery Furnace (Chapter 3) The state demands total allegiance (worship of the image). The faithful remnant refuses. God vindicates them not by keeping them out of the fire, but by joining them in it (the Fourth Man).

[C] Judgment on the King: Nebuchadnezzar (Chapter 4) The climax of the first half. The greatest king on earth is humbled into a beast-like state for seven periods of time until he acknowledges that "the Most High rules the kingdom of men."

[C’] Judgment on the King: Belshazzar (Chapter 5) The mirror image of Chapter 4. Another king acts in pride (desecrating the Temple vessels). He receives immediate judgment via the "Writing on the Wall," marking the end of the Babylonian era.

[B’] Persecution & Deliverance: The Lion’s Den (Chapter 6) The mirror image of Chapter 3. The state forbids prayer to Yahweh. Daniel refuses to hide his allegiance. God shuts the mouths of the lions, vindicating His servant and judging the conspirators.

[A’] The Four Empires: The Beasts (Chapter 7) The mirror image of Chapter 2. The same four empires are seen not as a glorious statue (man's view) but as chaotic beasts (God's view). The "Son of Man" receives the dominion that the beasts tried to seize.

III. THE HEBREW VISIONS (Chapters 8–12)

Focus: The Future of the Covenant People

Chapter 8: The Ram and the Goat A specific zoom-in on the conflict between Medo-Persia (Ram) and Greece (Goat). It introduces the "Little Horn" (Antiochus IV Epiphanes) who will attack the sanctuary.

Chapter 9: The Seventy Sevens Daniel studies Jeremiah’s 70-year prophecy. He prays a prayer of corporate confession. The Angel Gabriel reveals that Israel's restoration will take "Seventy Sevens" (490 units) to finish transgression and anoint the Most Holy.

Chapters 10–12: The Final Vision

- Chapter 10: The Prologue. The "War in the Heavenlies" reveals the spiritual conflict behind earthly politics (Prince of Persia vs. Michael).

- Chapter 11: The History. A detailed prophetic roadmap of the wars between the King of the North (Seleucids) and King of the South (Ptolemies).

- Chapter 12: The Resolution. The promise of the resurrection of the dead and the final reward for the wise who "shine like the brightness of the heavens."